In 1499 Antonio Grimani, as Admiral of the Venetian fleet, presided over its disastrous defeat at the hands of the Ottomans off the south-western coast of the Peloponnese at the battle of Zonchio. The Venetian maritime strongholds of Modon, Coron and Lepanto were lost. Grimani was conveyed back to the lagoon in leg-irons and condemned to perpetual exile on the Dalmatian island of Cherso. But he escaped to Rome, where, in 1493, he had paid Rodrigo Borgia an enormous sum to have his son Domenico made a cardinal; ten years later, in one of the greatest comebacks in Venetian history, Antonio was not only allowed to return home but elected Doge in 1521.

In 1499 Antonio Grimani, as Admiral of the Venetian fleet, presided over its disastrous defeat at the hands of the Ottomans off the south-western coast of the Peloponnese at the battle of Zonchio. The Venetian maritime strongholds of Modon, Coron and Lepanto were lost. Grimani was conveyed back to the lagoon in leg-irons and condemned to perpetual exile on the Dalmatian island of Cherso. But he escaped to Rome, where, in 1493, he had paid Rodrigo Borgia an enormous sum to have his son Domenico made a cardinal; ten years later, in one of the greatest comebacks in Venetian history, Antonio was not only allowed to return home but elected Doge in 1521.

Domenico’s appointment as Cardinal greatly enhanced the immensely wealthy Grimani family’s political standing in the Serenissima, as they established themselves as intermediaries between the Republic and the Vatican. But it was also decisive in enabling the Grimani to become collectors and connoisseurs on a princely scale. Numerous ancient sculptures were unearthed on the Grimani Roman estate on the Quirinale Hill. Domenico, a cultivated humanist, meanwhile amassed one of the finest libraries of the early Renaissance, collected gemstones, medals, and Italian and Northern artworks, including paintings by Raphael and Heironymus Bosch.

When Domenico died in 1523, he left some of his finest sculptures, his Netherlandish paintings and the famous Grimani Breviary to the Venetian state, a gesture perhaps intended partly to continue the rehabilitation of the family name after Antonio’s ignominious performance at the battle of Zonchio.

The next generation of the Grimani were also avid collectors. Giovanni Grimani, Antonio’s nephew, was made Patriarch of Aquileia in 1545, and in due course inherited the collections of his brothers Marco, Marino and Vettore. But any ambitions Giovanni had of further advancement in the Church were scotched by accusations of Protestant sympathies, and he devoted much of his life to transforming Palazzo Grimani into a residence-museum for his inherited and his own ever-expanding collections.

Inspired by contemporary ideas of the ancient Roman domus, he entirely remodelled the Palazzo Grimani, according to his own architectural plans, doubling its size with a large central courtyard and peristyle. He also called in Roman and Central Italian artists, notably Francesco Salviati and Giovanni da Udine, and later, Frederico Zuccari, to fresco and stucco the interiors.

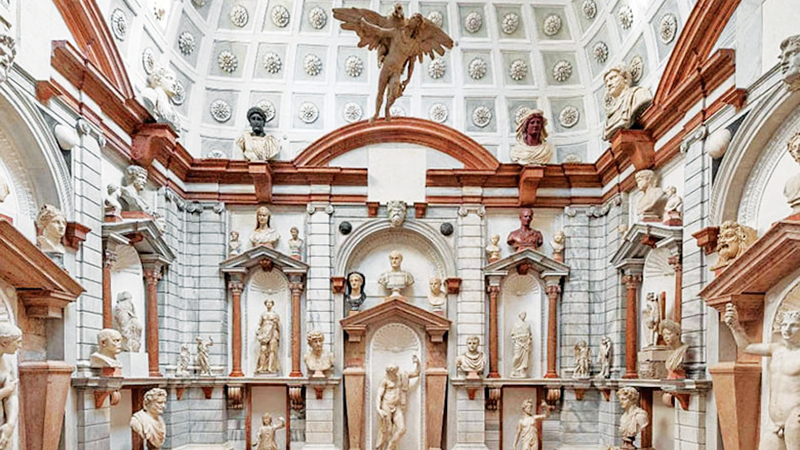

But the most astounding feature of the interior was La Tribuna, the sculpture gallery, with its soaring white, grey and red marbled floor and walls and coffered dome into which light floods from a four-sided lantern high above. This theatrical setting was devoted to displaying about 130 of Giovanni’s most precious marbles and bronzes in arches and niches and on brackets, with the final dramatic touch provided by a marble from Constantinople: Zeus in the form of an eagle carrying away the beautiful young shepherd Ganymede, suspended below the lantern. Unusually, the Grimani collection included a number of genuine Greek marbles, as opposed to Roman copies, thanks to Venice’s network of trading stations in the Levant and the fact that the city was then the principal emporium of sculptures arriving from the East.

Among early visitors to Palazzo Grimani was Henry III of France in 1573 and Alfonso d’Este, both of whom left admiring accounts of the experience. It continued to be one of the essential landmarks on the Grand Tour for over 200 years.

But it was also a vital resource for Venetian sculptors and painters, as is clearly reflected in the works of Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese and countless others.

In 1586 Giovanni Grimani made an act of donation before the Senate, presenting his collection upon his death to the State “for the memory of ancient things, and for the instruction and example of others”. This was conditional on a suitable setting being constructed for its display, similar to that of La Tribuna, in Piazza San Marco. This last proviso was never met, but the collection was transferred on Giovanni’s death in 1593 to the antechamber of Sansovino’s Biblioteca Marciana. It was opened to the public three years later, making it the first public sculpture museum since antiquity.

After the fall of the Republic, the sculptures were moved to the Doge’s Palace and then to the new Archaeological Museum, but partially returned to the antechamber of the Library in 1997. However, with restoration works going on there, and as a result of the inspired efforts of Daniele Ferrara, the director of the Polo Museale del Veneto, and Toto Bergamo, the director of Venetian Heritage, the sculptures have now returned to their original purpose-built space. Thanks to inventories made by the Serenissima’s secretaries at the time the sculptures were first moved, we have a remarkably accurate idea of which pieces were originally in La Tribuna, and even exactly where some were positioned. The collection will reside at the Palazzo Grimani for the next two years, for the first time in over four centuries. -Times Literary Supplement

Add new comment