Our earliest memories of the movies linger on the big details: wide landscapes, grand performances, and the perennial line between good and evil. Movies tend to indulge in these pleasures; they make concessions to what we want. Even the best directors find it hard to restrain themselves; they like to give in. More often than not, the films they make remain in our memories, purely because they are so well made.

Our earliest memories of the movies linger on the big details: wide landscapes, grand performances, and the perennial line between good and evil. Movies tend to indulge in these pleasures; they make concessions to what we want. Even the best directors find it hard to restrain themselves; they like to give in. More often than not, the films they make remain in our memories, purely because they are so well made.

Ben-Hur is a film like that. It might be the greatest epic film ever made, though in my list it comes well below Lawrence of Arabia, The Leopard, and The Godfather: Part II. What’s fascinating about it is that no one knows what it’s about. Reflecting on it around 20 years later, Charlton Heston, who played its hero, argued, “It’s a tale of people.” Elsewhere, Gore Vidal, who contributed to the screenplay but was never really credited, pointed to an erotic subtext in the plot: something Heston would later deny.

Ben-Hur is a film like that. It might be the greatest epic film ever made, though in my list it comes well below Lawrence of Arabia, The Leopard, and The Godfather: Part II. What’s fascinating about it is that no one knows what it’s about. Reflecting on it around 20 years later, Charlton Heston, who played its hero, argued, “It’s a tale of people.” Elsewhere, Gore Vidal, who contributed to the screenplay but was never really credited, pointed to an erotic subtext in the plot: something Heston would later deny.

The interplay between the hero and the antagonist, who happens to have been a childhood friend of the hero, is the most intriguing aspect of the plot: why do relations between them sour so much, and so suddenly? Vidal suggested that they had been more than friends as children, and that the straining of relations between them could be read as a case of amour fou and chagrin d’amour. Even Wyler, who is supposed to have given Vidal the green light, later denied this. But then Ben-Hur may be one of the few films in Hollywood history where the screenplay buries so many themes, allowing us so much interpretation.

Absurd plot

Burt Lancaster turned down the role that went to Heston, because he thought the script boring. Gore Vidal called the plot absurd, contending that “any attempt to make sense of it would destroy the story’s awful integrity.” This is probably why the scriptwriters tried to add a psychological dimension to the plot, and why, until Christ makes an appearance, it rests entirely on Ben-Hur’s relationship with his friend. Yet it’s perhaps a testament to its awful integrity that no one knows who wrote what, let alone what was written. This may explain why the screenplay gained controversy, and why it didn’t win an Oscar.

Burt Lancaster turned down the role that went to Heston, because he thought the script boring. Gore Vidal called the plot absurd, contending that “any attempt to make sense of it would destroy the story’s awful integrity.” This is probably why the scriptwriters tried to add a psychological dimension to the plot, and why, until Christ makes an appearance, it rests entirely on Ben-Hur’s relationship with his friend. Yet it’s perhaps a testament to its awful integrity that no one knows who wrote what, let alone what was written. This may explain why the screenplay gained controversy, and why it didn’t win an Oscar.

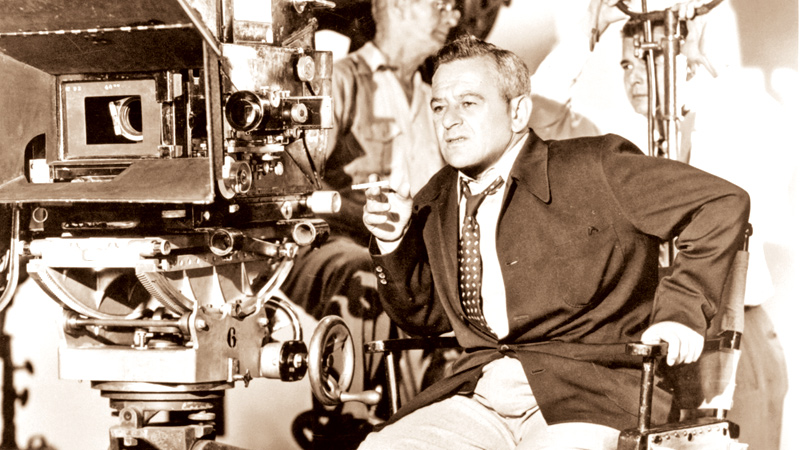

Ben-Hur was directed by William Wyler, whose career spanned more than half a century and who lived through the silent era. Wyler’s version of Ben-Hur wasn’t the first: it was the third. It was also the first in sound and in colour: two points that made it more difficult to film than the previous adaptations. Budgeted at seven million dollars, it ended up costing more than 15 million. The pressures were such that, when asked whether he enjoyed acting in it, Charlton Heston admitted he hated the experience. This was just as well: if audiences didn’t take to it well, MGM would have gone bust.

Fortunately, these fears proved to be unfounded. Ben-Hur ended up grossing almost 150 million dollars, becoming the second-highest box-office hit in history after Gone with the Wind. It went on to clinch 11 Oscars from a total of 12 nominations, the highest tally for a film, a record that remains unbroken today. It salvaged MGM’s prospects and proved Wyler’s capabilities, though he never made a film quite like it again. More importantly, it confirmed Heston’s forte in playing history’s greatest larger-than-life characters; he had played Moses in The Ten Commandments three years earlier, and would go on to play John the Baptist, Arthur Gordon, El Cid, Michelangelo, and Mark Antony.

Musical story

Yet what’s interesting about Ben-Hur, more than its intriguing but ultimately confusing plot, is that it remains to the epic film what West Side Story is to the musical: everyone talks about it, and everyone more or less likes it, but not everyone considers it as a benchmark for the genre. When you talk about the epic film, you immediately remember John Ford’s Westerns, Cecil B. DeMille’s religious parables, and David Lean’s collaborations with Sam Spiegel and Robert Bolt. You do remember the rowing galley and the chariot race sequences from Wyler’s film, but that’s about it: on the other hand, you remember five or six scenes from Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. Even Ryan’s Daughter, for all its technical and narrative faults, sticks to our memories more clearly. How so?

Yet what’s interesting about Ben-Hur, more than its intriguing but ultimately confusing plot, is that it remains to the epic film what West Side Story is to the musical: everyone talks about it, and everyone more or less likes it, but not everyone considers it as a benchmark for the genre. When you talk about the epic film, you immediately remember John Ford’s Westerns, Cecil B. DeMille’s religious parables, and David Lean’s collaborations with Sam Spiegel and Robert Bolt. You do remember the rowing galley and the chariot race sequences from Wyler’s film, but that’s about it: on the other hand, you remember five or six scenes from Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. Even Ryan’s Daughter, for all its technical and narrative faults, sticks to our memories more clearly. How so?

It may be that, like West Side Story, Wyler’s film hasn’t aged well. This has to do with its characters. Judah Ben-Hur’s transformation from vengeance to forgiveness isn’t half as complex as T. E. Lawrence pondering the East or Yuri Zhivago reflecting on the October Revolution. This is something Vidal claimed he addressed when he brought in an erotic aspect to the childhood friendship between hero and villain, but even if you watch the early scenes with that aspect in mind, Ben-Hur ends up being a morality play about retribution, forgiveness, and redemption. It’s Classics Illustrated for Sunday School: more complex than The Ten Commandments or The Robe or King of Kings, but just as self-righteous.

In an era where heroes were becoming increasingly hard to define, there’s hardly any ambiguity in Ben-Hur. The heroes are utterly heroic and the villains utterly dislikeable. This is unlike a film like Lawrence of Arabia, which reverberates so strongly because we identify with the hero’s flaws, rather than his strengths.

Lean’s hero is stubborn, unyielding, and unrelenting. Half the things he does lack reason or logic: he’s pushed by his great love for the Far East, by his desire to be a part of it all. By contrast, despite his best attempts, Charlton Heston manages to turn Ben-Hur into a Jewish prince with an overarching passion to take revenge on his Gentile tormenter. That may have won Heston an Oscar and denied Peter O’Toole, who played Lawrence, one, but it helps us distinguish between two different cinematic visions.

Personal visions

To say this is to remember that the Cahiers du Cinema critics and directors had a dim view of Wyler in the 1960s. In an intriguing essay, Andre Bazin concluded or rather complained that there was nothing remarkable about Wyler’s work: “it is more difficult to recognize the signature of Wyler in just a few shots,” he noted. This was not a compliment: the Cahiers circle looked up to directors whose personal visions were deeply embedded in their works. A director like Wyler presented a problem there because, for Bazin, while there was “a John Ford style and a John Ford manner,” “Wyler has only a style.”

This is of course simplistic and reductionist, but it is not entirely invalid. And it may explain why Ben-Hur feels rather lifeless, despite its grandiloquent vistas and performances. For the truth of the matter is that Ben-Hur lacks the charm and vitality of even the morally simplistic religious epics of the 1950s. A film like DeMille’s The Ten Commandments may contain too much self-parody to be taken seriously, but it’s fun to watch: you never get tired of imitating Anne Baxter’s invocation of the hero’s name (Maw-ses). Ben-Hur, on the other hand, is utterly serious, and is meant to be taken seriously from start to finish.

In a way Wyler was destined to make movies like Ben-Hur. A product of Hollywood’s ubiquitous studio system, Wyler made more than 25 silent films and more than 30 sound films. Like George Cukor, he became an actor’s director; his body of work contains some of the most memorable performances in cinema history.

Because he was able to work anywhere, he got a wide range of material to choose from: from Charlotte Bronte (Wuthering Heights) to Lillian Hellman (The Little Foxes and The Children’s Hour) to Henry James (The Heiress) to Jessamyn West (Friendly Persuasion).

Like Fred Zinnemann, he never stopped working, and wound up as one of the few directors from Hollywood’s Golden Age to work their way beyond the 1960s. He died in 1981.

One little anecdote deserves mentioning here. Wyler has two connections to the Sri Lankan cinema and Lester James Peries: Friendly Persuasion competed with Rekava at Cannes in 1957, while The God King, which Peries made 20 years later, employed Gus Agosti, Wyler’s assistant for Ben-Hur, at 500 dollars a week for 16 weeks. Agosti had a big reputation: he had overseen Ben-Hur’s chariot race sequence.

Peries was puzzled, however: how is it that Agosti never struck his own path as director? His reply was interesting in its own way: “There are many good directors, but very few good assistant directors.”

Add new comment